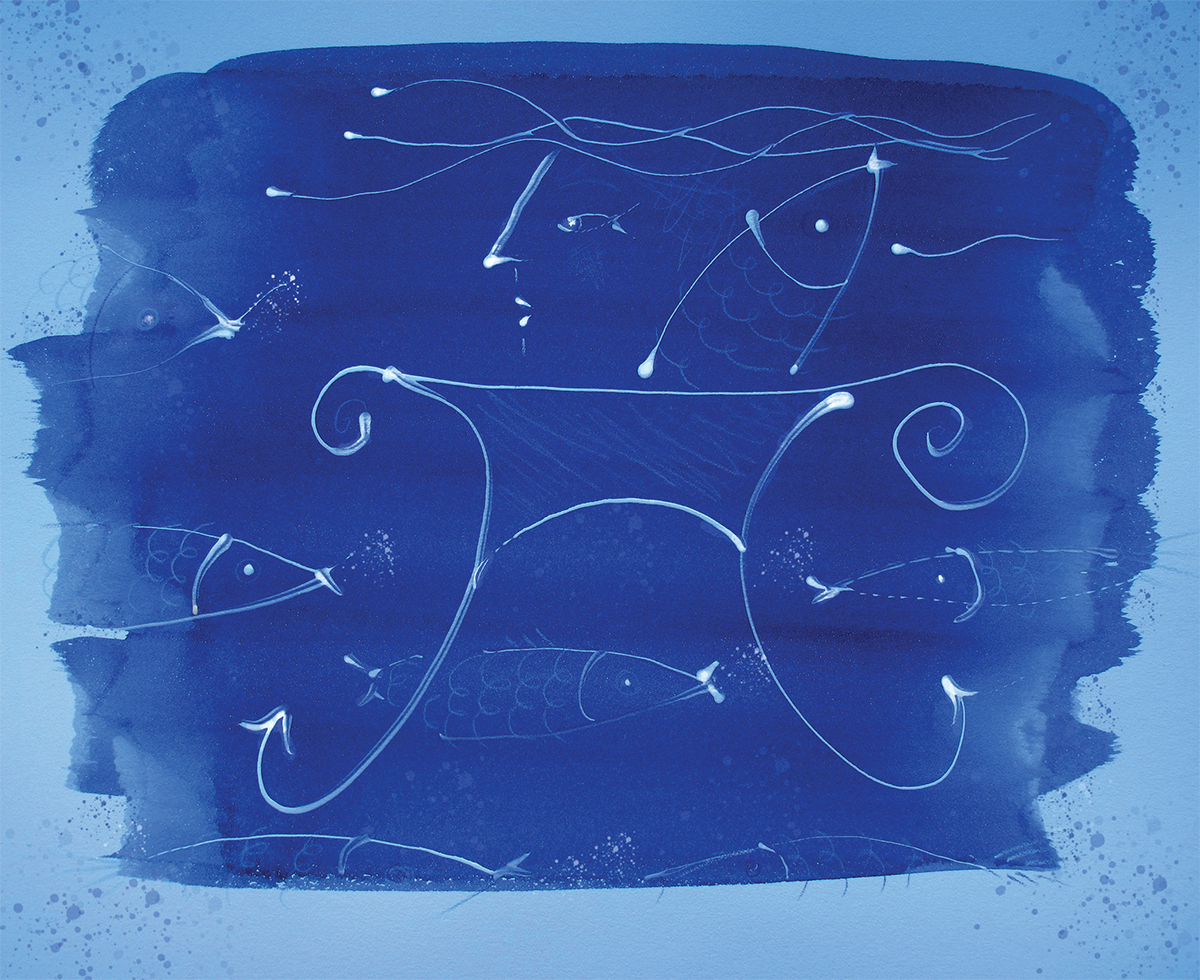

Illustration by Alexa Grace

Illustration by Alexa Grace

A writer’s journal

A Maine Life

Haunted by Waters

The Rio Colorado, a jungle river, carries huge loads of forest flotsam for almost a mile through Costa Rica into the Caribbean before its current wearies, the silt load falters, and the ocean water abruptly clears to luminescent turquoise. The sea floor is invisible, but you can easily see tarpon and crevalle jack swimming 40 feet or so under the skiff. A manta ray the size of a big throw rug glides by. Sharks, too—very, very large sharks.

My son and I were celebrating his college graduation on a Costa Rican fishing vacation. This day, our fourth in the hot sun on a windless ocean, had been intensely wearying and even more intensely satisfying. We each had hooked, landed, and released six tarpon, one of the angling world’s top trophies. The smallest weighed 110 pounds, the largest close to 160. With leaps that take them nearly 10 feet out of the water and soundings that take them to the bottom, they are tenacious and tough. Getting them to the boat is very hard work and worth every drop of sweat to do it.

We decided—and Cesar, our guide, agreed—that it was time to quit. But I made one more cast anyway, as anglers always do, and a new adventure began. Something slammed my bait and, despite my every effort, just kept taking line—towing the boat, in fact. My 300 yards of line disappeared in a blur off the reel’s spool and then broke off. We sat stunned. There were no whales around, but some creature of very large size, commensurate strength, and presumed ferocity was. And for 10 minutes or so, we had connected with it. A leviathan, and a mysterious one at that.

That’s the thing about waters and fishing. You never know what lurks in the murky depths beyond your ability to see or sense it. A bit like life, I think. And just like life sometimes, it is frightening—the not knowing what that vastness holds in store. But still, you keep looking into that abyss, searching, wondering, imagining.

I caught my first fish, when I was 6 or so, on a worm-baited hook dangling a few feet below a red-and-white bobber. The bobber obligingly bobbed, I yanked, and a 6-inch-long sunfish flopped at my feet. Up to that moment, I didn’t know what existed below the pond’s tranquil surface, but from then on, I was hooked far more firmly and lastingly than that poor sunny. And I have never lost that sense of mystery about what lies beneath. Fishing, a wise soul once wrote, is a perpetual series of occasions for hope. And exhilaration and despair, fear and bravado, and a host of thoughts and feelings, a gamut I run every time I wet a line.

An adage has it that “meditation and water are wedded forever,” and I have spent countless hours lost in thought while trolling the lake.

I moved to Maine because I fell in love with a lake, deep and dark and capable of astounding me every time I visit it. There are boulders the size of houses, shoals of sharp-edged granite slabs in places where they shouldn’t be (like in the middle), and winds that quickly can distort a mirrored surface into a maelstrom with waves 6 feet high or more. Violent storms erupt with little warning, bringing lightning and drenching rains. No leviathans capable of towing boats, but plentiful aquatic denizens of more modest dimensions. Good fishing, in other words. And always just that slight sense of danger.

The lake is almost 18 miles long, and its twists and turns would make even the best gerrymandering politician green with envy. After all these years, I still discover new coves, new sights, find new things to ponder. Yet the place seems eternal, unchanged. Overlooked by the world and time, it welcomes solitude, a respite from the cares and woes of the everyday world. Days have passed when I have not seen another human being.

An adage has it that “meditation and water are wedded forever,” and I have spent countless hours lost in thought while trolling the lake. A ferocious strike by a smallmouth bass interrupts every so often, but examining this particular piscatorial wonder of nature, resplendent in spawning colors, and reflecting on its indomitable will to resist and escape always leads to more reverie about this wild world and my modest place in it.

The stygian darkness of the surrounding spruce forest is broken by a shaft of light where a deadfall lies. On the shore, a huge boulder, one I have watched for more than 50 years, finally has calved, split neatly in two by ice and time. And beneath my boat, there is another world existing in ways I can only guess at. Landlocked salmon gather in the inky depths to escape the sun’s warmth. Trapped by the Ice Age eons ago, they are Atlantic salmon without an ocean to return to. In all these years of fishing this lake, I have landed just one. A very homely freshwater cousin of the cod, a cusk, lives there too, also prisoner of the Ice Age. I have never seen one.

Nor have I glimpsed a local version of a Loch Ness Monster, yet the lake is large enough and deep enough and wild enough...who knows what lives down there? After all these years, I still wonder, and imagine, and sometimes half believe that a leviathan lurks in wait in those inky depths, too.

Maybe that persistent belief is the true allure of waters, and of fishing: that there are wonders unseen, but maybe one magic day you will see them.

—Ron dePaolo ’64

Penobscot, Maine

Ron dePaolo enjoyed a distinguished career as a journalist for Life and Business Week,

and his articles have been published in Audubon, Smithsonian, and Outdoors, among others.